Why I take FASD training to the NT

Occasionally, I am asked why I provide FASD training in the Northern Territory, despite residing in Melbourne. It’s a valid question, and the answer involves a backstory that I’d like to share with you. Please note that this narrative is rather lengthy, so feel free to skip ahead if you wish.

Jade Scott, me and Dr Annette Connolly at Monash Hospital, FASD Awareness Day 2022

In 2006, I packed up and headed to Alice Springs as a child protection team leader. While it wasn’t my first trip to Alice, having been there for the Pine Gap protests in 1987 and attending a cultural program a few years later, it was my first time living there.

The job opportunity was too good to pass up, and I felt it was the right time to make the move from Melbourne with my 6-year-old daughter. Little did I know how challenging it would be and how much I had to learn.

Working in child protection with some of the most vulnerable and disadvantaged families in Australia required skills and understanding that I didn’t have at the time.

As a team leader in out-of-home care, I was responsible for children living in either foster or kinship care, many of whom were on remote communities, and staff were often travelling. I was in the office supervising staff, going to court, and doing case plans.

A significant number of children who were placed in out-of-home care had been exposed to alcohol in pregnancy.

Back then, paediatricians could diagnose Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) in children who displayed distinct facial features, as well as met specific criteria related to their growth and cognitive abilities.

However, children who did not exhibit these facial features were unable to receive a diagnosis of FAS, even if they had significant developmental and learning challenges. In the United States and Canada, there were alternative diagnoses available for such children.

However, in Australia, it would take another ten years before the diagnosis of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) would be introduced.

Children were falling through the gaps. There were no guidelines or policies about how to support children affected by prenatal alcohol exposure. There were few Australian resources available, and child protection workers had no FASD training or access to information.

Looking back on that time, it’s hard for me to recall achievements rather than mistakes. In 2007, the intervention started, and it imposed alcohol restrictions even on communities that did not ask for them.

However, being new to the Territory, I did not fully understand the negative impact on Aboriginal communities especially in terms of the loss of self-determination.

While there was a reduction in alcohol and safer dry communities for children, income management was demoralising, paternalistic and deeply racist which has now shown to have caused low birth weight babies in Aboriginal mothers affected.

Fortunately, I had great colleagues among the Aboriginal Community workers like Dawn Ross, Vicky Haddon, and others, who shared their wisdom and experience, provided support, and gave me honest, valuable feedback so that I could learn from my mistakes.

Following a difficult case involving a child with FASD and conflicting professional opinions, I applied for a Churchill Fellowship to travel to the US and Canada and study models of support for children with FASD in out-of-home care. During my 10-week trip in 2009, I visited First Nations agencies, FASD diagnostic clinics, researchers, and other FASD services.

I began my journey at the international FASD conference in Victoria, BC, where I met a few Australians who were active in FASD research and advocacy. After the conference, I visited the Asante Centre in Maple Ridge, Vancouver, and attended a 3-day diagnostic clinic with a multidisciplinary team.

Chris Rogan was also there with members of her team from New Zealand, who were undergoing FASD training at the centre. Chris went on to establish the first FASD multidisciplinary team training in NZ.

The Asante team – Julianne Conry, clinical Neuropsychologist, Dr Kwadwo Asante, Audrey Salahub, Krystal Bodaly; and with Chris Rogan and team.

The Asante team – Julianne Conry, clinical Neuropsychologist, Dr Kwadwo Asante, Audrey Salahub, Krystal Bodaly; and with Chris Rogan and team.

During my visit to the University of Washington in Seattle, I had the privilege of visiting the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) clinic, which was managed by Susan Astley Hemingway. Along with Sterling Clarren, Susan had created the FASD 4-digit code, which is a classification system that captures the range of impairments that can occur due to prenatal alcohol exposure.

I was impressed by Susan’s clinic data, which showed that the rate of FASD diagnosis among children in care had declined in Washington State, as education about the risks of alcohol in pregnancy had increased. This reduction was attributed to the increased education on the risks of consuming alcohol during pregnancy.

I was also struck by the mandatory warning stickers placed on the back of every bathroom door in places where alcohol was sold – it showed how far ahead the States was in raising awareness of risks of alcohol in pregnancy.

In Seattle, I also had the pleasure of meeting Therese Grant, who pioneered the Parent-Child Assistance Program (PCAP) and Nancy Whitney, the Clinical Director.

This program has reduced the incidence of FASD by providing a relationship-based home visitation model for women at high risk of an alcohol or drug-affected pregnancy. I was so impressed by this model, which has been implemented all over North America, and I felt this was something I wanted to bring back to the NT.

Therese also introduced me to Professor Ann Streissguth, a co-author on the first paper in the Lancet describing the then termed “FAS”. Ann was near retirement but was mentoring the PCAP program.

One of the highlights of my Churchill Fellowship trip was visiting the Lakeland Centre for FASD in Cold Lake, Alberta, for several days with Audrey McFarlane, who is now the executive director of the Canadian research network CanFASD.

Cold Lake was a town with a population similar in size to Alice Springs. The centre had a multidisciplinary diagnostic team and served a number of regional and remote First Nations communities by providing visiting FASD diagnostic services, family support post-diagnosis, and other activities such as summer camps.

While I was there, Audrey was working on a proposal to build housing for young people with FASD to support them into adulthood. I found this visit inspiring and was impressed by the scope of services offered by the centre.

In Juneau, Alaska, I was hosted by Ric Iannolino, the FASD Clinic Coordinator with the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (CCTHITA). Ric had provided training to thousands of Alaskan social workers and was a resource for the whole community.

Ric took me to visit the range FASD services available in the region, including FASD services embedded in First Nations Health services and early childhood services.

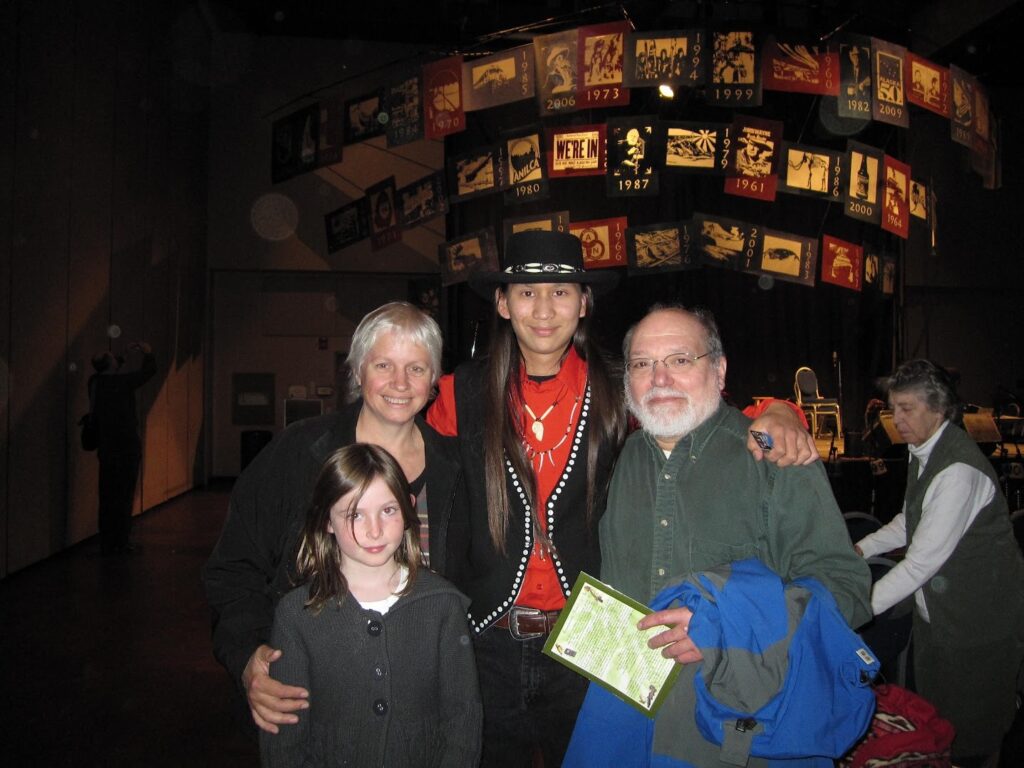

Ric also introduced me to Morgan Fawcett, a young First Nations man who was a talented flute player and FASD advocate. Ric also explained the 3M model – mentoring, role modelling, and monitoring – a program designed to support First Nation Alaskan young people back home after they had been placed in residential care interstate.

With Morgan Fawcett, Ric Iannolino and Ruby at a Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska ceremony.

Visiting Hoonah, a Tlingit community on Chichagof Island with Ric Iannolino

My focus was on finding innovative models of supporting children with FASD in child protection services. One of the services that stood out was Surrounded by Cedar in Vancouver, which supported First Nations children in out-of-home care and had taken over the guardianship role from the state government.

The staff were very proud to have taken on this responsibility, and it was an incredible service. Alberta Children’s Services had initiated a FASD strategy for the province with engagement of 13 government departments and agencies.

I also had the privilege of attending two days of training with Donna Debolt, who had trained an estimated 10,000 workers across Canada in FASD-related skills. Her teachings still influence my work today.

She introduced me to the work of Dorothy Badry, a social worker and professor, and the Community of Practice, which demonstrated the capacity to improve placement stability for children with FASD.

After my visit to the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) clinic in Seattle, I returned home with a greater realization of the significant need for prevention, diagnosis, and support services for individuals affected by FASD in our community.

Witnessing the benefits of multidisciplinary diagnosis, initiatives such as the Parents’ Child Assistance Program (PCAP), and the FASD Key Workers, I came to understand the crucial role of FASD training for all professionals involved in the sector.

In addition, I observed that embedding FASD services within Aboriginal-controlled healthcare facilities led to reduced shame and stigma around the condition.

Despite my eagerness to share my findings and experiences, my position as a public servant limited my ability to speak publicly about the limitations of government services. Instead, I focussed on sharing what I had learnt with my managers and with community based organisations.

I delivered a paper to the Australia Pacific Conference on Child Abuse and Neglect (APCCAN) in Perth in 2009, and gave a presentation to the Department of Health executive in Darwin, including the CEO and health advisors.

Unfortunately, my efforts were met with a resounding lack of interest. I was told that we were only seeing about 5 children born with FASD a year in the Top End, based on Harris and Bucens’ study in 2003, and that the focus should be on prevention rather than treatment. Overall, the response was disappointing and left me feeling frustrated with the lack of urgency and action on FASD by government.

I realise now that I was filled with an idealistic energy and a strong desire to take action – the eye-opening experience had left a significant impact on me, and I became acutely aware of the severe consequences of ignoring FASD.

The thought of such injustices kept me up at night, and I couldn’t ignore the urgent need for action. In Canada I had heard some incredibly sad stories of young people and adults with FASD who had experienced tragic events or committed terrible crimes, or had caused harm to others in situations that could have potentially been avoided, had their disability been recognised and had they received the support and supervision they needed.

In 2009, I joined forces with other concerned professionals in Alice Springs who shared my passion for addressing FASD.

Together, we formed a steering group that included representatives from various organizations such as Alcohol and Other Drug Services Central Australia (ADSCA), NT Families and Children, Alice Springs Hospital, Central Area Coordination, Congress, Holyoake and the GP Network. ADSCA provided us with some project funding, which allowed us to raise awareness about FASD.

Our first event was a stall at Alice Plaza for International FASD Awareness day on September 9, 2009.

We also invited Professor Elizabeth Elliott, an Australian FASD expert, and Vicki Russell from NOFASD to Alice Springs to provide professional development and training.

We planned a series of events for February 2010, including five events over three days, for carers, professionals, and Alice Springs Hospital staff. The events culminated in a full-day community forum where Josie Ward and Penny Bridge from the Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service shared their FASD project.

Maureen Carter and June Oscar from Marninwarntikura Women’s Health Service in Fitzroy Valley showed a new documentary film, Yajilarra, about their campaign to reduce the harmful impacts of alcohol in their community.

The working groups generated recommendations, and we submitted a project report to the Department of Health. The report emphasized the need for more information and training for health professionals, as a first step in developing a local action plan.

“The issue of FAS is not new in Central Australia, and had been previously raised … Yet despite a level of awareness among health providers, there appeared to be a lack of resources readily available to inform those in contact with the at-risk population, and no regular training.

It was felt that the potential impact of FAS and FASD in the long term may be underestimated and that increased education, awareness and targeted service delivery could both reduce the impact of FASD and improve the lives of affected individuals.“

Alice Springs FASD project report, February 2010

An opportunity arose and I transferred to a new role as manager of the child protection office in Nhulunbuy. It was a significant change for me, as I had to learn about Yolgnu culture and adapt to a new environment. However, I was fortunate to have the support of a team of Aboriginal community workers, who helped me navigate the challenges and understand the local context.

The community had its own system of alcohol restrictions that applied to everyone, and had been in place prior to the Intervention.

To purchase alcohol, permits were required for all residents and take-away liquor was limited, resulting in a reduced volume of alcohol in the community. However, despite these restrictions, FASD remained an issue due to the availability of alcohol from outlets in town.

When I returned to the 4th International FASD conference in Vancouver in March 2011, I had the opportunity to meet more Australians who were working in the field of FASD including Kerryn Bagley, a social worker from New Zealand who was doing her PhD on FASD and social work.

We shared a common practice approach and were eager to disseminate this information. Kerryn attended training with Diane Malbin in Portland, Oregon, on the Families Moving Forward model, and became the only accredited facilitator in Australia at that time.

While in Nhulunbuy, I discussed the need for FASD training for child protection workers with my manager who agreed that I could run some FASD training workshops at different sites.

I also proposed a research project to review the files of children who had open child protection files and those in care to determine how many children had experienced prenatal alcohol exposure. The project was approved, and I continued it even after I moved back to Melbourne at the end of 2011.

In 2011 the Australian Government House of Representatives launched an inquiry into FASD. I made a submission based on my findings from my Churchill Fellowship. Although I was no longer employed by the NT government, I still felt strongly about the issue and wanted to contribute to the inquiry.

There were several submissions from NGOs, peak organizations, and individuals in the NT, but surprisingly, there was nothing from the NT government. The report, titled “FASD: The Hidden Harm,” was released in November 2012, and its first recommendation was the development of a national FASD action plan based on the report’s findings.

After returning to Melbourne, I found work in child protection since there were no FASD jobs available. Even though it was a full-time job, I would occasionally take leave and travel back to the NT to conduct FASD workshops in Alice Springs, Darwin, and sometimes Nhulunbuy and Katherine.

I decided to start a FASD consultancy in 2014 after resigning from my job in child protection. Even though FASD was a significant issue in Victoria, it was much less recognized than in the NT. To generate interest, I sent information sheets about FASD to every child protection office, school, foster care agency, and peak body in Melbourne.

I even met with training coordinators in child protection and youth justice to discuss training. Although people seemed interested in FASD, they didn’t follow through with attending workshops despite my efforts to advertise and promote them at conferences and events.

To continue spreading awareness about FASD, I scheduled workshops in Alice Springs, Darwin, and occasionally Nhulunbuy and Katherine, traveling up three or four times a year. I was sometimes self-conscious about why I was doing this work and if people knew anything about me.

I made sure to respect the local agencies and not duplicate what was already in place, but also knew that there was a demand for more FASD training from policy makers, teachers, disability workers, lawyers, therapists, and child protection workers who didn’t receive adequate FASD education in their basic training.

I had a regular training arrangement with Berry Street in Melbourne, where I presented a full-day workshop that I had been running for about four years. The workshop covered the basics of FASD diagnosis, the lifespan approach, and case studies for case management. I drew on what I had learned overseas, particularly in relation to children in care and in the justice system.

In one workshop, I was really challenged by one of the participants, Tony. He was getting agitated with some of the things I was saying. Looking back, I was probably being too black and white about things, and now I would qualify my statements a bit more. But I was explaining that we can’t expect young people with FASD to learn things the same way other kids learn things.

Tony was saying, “You can’t say that. You can’t say they can’t learn.” So we talked through the issue, and I tried to explain it differently, but I could see he wasn’t happy. At the end of the day, when we went around the room and everyone was saying something they would take away from the workshop, we got to Tony, and he said, “Well, I’m really angry,” and I just went cold inside. And then he said, “I’m angry this is the first time I’m hearing about this.” He couldn’t believe that with so many children affected, we weren’t doing more about it.

Tony was concerned because one of the things we talked about in the workshop was that the young people they worked with needed to be independent at 18, and my view was that young people with FASD can’t be. The participants said, “Well, there’s no other option,” and I said, “That’s the point.

That’s what we need to advocate for, and what we need is for workers like yourselves to understand FASD, so you can talk to your managers and gather the evidence to take to government, to demonstrate that young people with FASD cannot be independent at 18, and that our system needs to change. Our options need to change.” That’s a hard message to deliver, because I’m sending people away from training feeling like they don’t know what to do.

They know that the young person they are supporting can’t manage in private rental, but they don’t have any other option for them. Back then, the aftercare options were limited, and a young person might get a bit of support to get set up in housing and a worker they can contact but not much more. That’s why the Home Stretch project extending care was so important for all young people, but especially young people with FASD.

Drumming up interest in FASD in May 2014

After the workshop, Tony reached out to me and expressed his desire to do more to address FASD. His agency worked in partnership with Rumbalara Aboriginal Coop in Shepparton and he asked me to help design and facilitate a full-day workshop at Rumbalara in November 2014.

Tony organized the logistics of the workshop, while I co-facilitated with a colleague, Jody Barney. Jody is a Deaf Aboriginal/South Sea Islander woman who is a leader in the disability field, and we had previously met and run workshops together for VACCA.

The workshop was a huge success, with approximately 200 attendees, including Andrew Jakomos, the Aboriginal Children’s Commissioner, and Sharman Stone, a local MP who had chaired the FASD Senate Inquiry in 2012.

The workshop was well received by the Aboriginal community members and it was clear this was an issue that was impacting the community. Later the Goulburn Health FASD clinic was later established in Shepparton through Patches Paediatrics.

Rumbalara Aboriginal Co-operative FASD forum, November 2014

At the First Australian FASD conference in Brisbane, 2014

I had a regular training arrangement with Berry Street in Melbourne, where I presented a full-day workshop that I had been running for about four years. The workshop covered the basics of FASD diagnosis, the lifespan approach, and case studies for case management. I drew on what I had learned overseas, particularly in relation to children in care and in the justice system.

In one workshop, I was really challenged by one of the participants, Tony. He was getting agitated with some of the things I was saying. Looking back, I was probably being too black and white about things, and now I would qualify my statements a bit more. But I was explaining that we can’t expect young people with FASD to learn things the same way other kids learn things.

Tony was saying, “You can’t say that. You can’t say they can’t learn.” So we talked through the issue, and I tried to explain it differently, but I could see he wasn’t happy. At the end of the day, when we went around the room and everyone was saying something they would take away from the workshop, we got to Tony, and he said, “Well, I’m really angry,” and I just went cold inside. And then he said, “I’m angry this is the first time I’m hearing about this.” He couldn’t believe that with so many children affected, we weren’t doing more about it.

Tony was concerned because one of the things we talked about in the workshop was that the young people they worked with needed to be independent at 18, and my view was that young people with FASD can’t be. The participants said, “Well, there’s no other option,” and I said, “That’s the point.

That’s what we need to advocate for, and what we need is for workers like yourselves to understand FASD, so you can talk to your managers and gather the evidence to take to government, to demonstrate that young people with FASD cannot be independent at 18, and that our system needs to change. Our options need to change.” That’s a hard message to deliver, because I’m sending people away from training feeling like they don’t know what to do.

They know that the young person they are supporting can’t manage in private rental, but they don’t have any other option for them. Back then, the aftercare options were limited, and a young person might get a bit of support to get set up in housing and a worker they can contact but not much more. That’s why the Home Stretch project extending care was so important for all young people, but especially young people with FASD.

In March 2014 the Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory established a Select Committee on Action to Prevent Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. Since I was still in touch with my DCF manager, I prepared a submission to the Committee based on this research on behalf of DCF.

The Northern Territory Council of Social Service (NTCOSS) also engaged me to work on their submission, and I made a personal submission to the inquiry, which allowed me to incorporate ideas from my Churchill Fellowship report. Ultimately, the three submissions were referenced extensively in the report, The Hidden Disability, published in February 2015.

In the lead up to the Action Plan, the Australian government ran a consultation in Melbourne which was the first time some of the people working in FASD in Victoria had come together.

This included Kerryn Bagley who was now living in Victoria, Jane Halliday and Evi Muggli who were working on the Asking Questions about Alcohol in Pregnancy (AQUA) study at MCRI, Cheryl Dedman, NOFASD Board member and carer, Dr Katrina Harris (who had written the first study on FAS in NT in 2003) who headed of Developmental Paediatrics at Monash Health, and Kellie Hammerstein from Aboriginal Health at Monash.

A loose network was formed, and later formalised in 2017 as the Victorian FASD Special Interest Group (or SIG) with the goals to raise awareness of FASD and in Victoria, to collaborate and share information, and to support development of FASD research and program development.

Members of the Victorian FASD SIG attended a FASD Roundtable at Shepparton in October 2019.

International FASD Awareness Day, Royal Children’s Hospital, September 2018

In late 2015 I resumed FASD training for child protection workers and youth justice workers in the Northern Territory as part of the professional development calendar for DCF. I would come up for a week, run a child protection workshop, offer a general workshop for the public, and provide a free in-service to a local organisation such as the Northern Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency (NAAJA).

I was now working in the community sector, managing out of home care programs including permanent care and adoption for Uniting Vic Tas. Overseeing the permanent care program brought me into contact with many children affected by FASD, mostly undiagnosed, and placement stability was a real concern.

This experience reinforced the importance of professional training, so I delivered workshops for my colleagues including other permanent care teams. We also integrated FASD screening in our processes. I spent 4 years in this role and met some amazing colleagues.

However it was almost impossible to access diagnosis, other than through private providers such as Dr Harris.

Things really took off in 2016, with the publication of the Australian Guide to the Diagnosis of FASD, the establishment of the FASD hub, the funding of diagnostic clinics, research, and funding for organisations such as NOFASD to deliver services and develop resources under the National FASD Action Plan.

The VicFAS SIG arranged several events to raise awareness of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) on International FASD Awareness Day. In 2018, the team organized a full-day workshop at the Royal Children’s Hospital, which was attended by 280 people.

In 2020, Kerryn Bagley, who now works at the Living with Disability Research Centre at La Trobe Uni, obtained funding for a webinar targeting professionals. We co-facilitated this webinar, which was attended by more than 600 people from Australia and New Zealand.

In 2019, Dr. Katrina Harris approached me with an exciting opportunity to help set up the first statewide FASD diagnostic service in Victoria at Monash Children’s Hospital. I was thrilled to join the team and be a part of this important initiative, which was my first actual job in a FASD role. At our launch event, we had the pleasure of hosting Dr. Dorothy Badry from the University of Calgary, and I also organized a forum with Dr. Badry and senior practice leaders from DFFH Child Protection.

Dr Katrina Harris, Dr Kerryn Bagley, me, Professor Dorothy Bagley and Dr Ali Crichton at the VicFAS launch.

Currently, I work part-time in the diagnostic service and have contributed to the assessment of over 100 children, with more than half of them being in out of home care.

As part of my role, I recorded a video discussing the role of social workers in FASD diagnosis, which is available on the FASD Hub. Additionally, I provide regular education sessions to community agencies, including child protection services in Victoria.

I find this work incredibly fulfilling and am grateful to be part of a team making a positive impact in the lives of children and families affected by FASD.

In 2022, I began a project with the Australian Childhood Foundation to integrate Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) into the organization’s well-established trauma-informed practice.

As part of this project, we established a FASD clinic in Darwin, organized webinars and events, and facilitated sessions on FASD and trauma at the International Childhood Trauma Conference in 2022. I am involved in the FASD Guidelines Development Group, working alongside Natasha Reid and her team at UQ to provide a social work perspective to the review of the Diagnostic Guidelines.

Dr Natasha Reid, Nicole Hewlett, Dr Liz Elliott and me at the APSAD Conference Darwin October 2022

With Dr Vanessa Spiller at the International Childhood Trauma Conference, Melbourne 2022

Now, for the first time since COVID, I have been able to resume training practitioners in the NT. I feel fortunate to work alongside other educators who are passionate about FASD, such as Sophie Harrington from NOFASD, Psychologist Dr Vanessa Spiller who offers excellent online training and resources.

I’m indebted to friends like Jess Birch, a FASD advocate and lived experienced educator. I also want to acknowledge the ground-breaking work of colleagues like the deadly Nicole Hewlett, who led the development of the Australian FASD Indigenous Framework.

I highly recommend reading this publication, which is the first of its kind in the world. We are incredibly fortunate to have a dedicated community of individuals committed to mitigating the effects of FASD.

It is critical to redress the harms from colonization, which have laid the foundations for FASD in Aboriginal communities.

While by no means a panacea to addressing FASD in every Aboriginal community, the Australian FASD Indigenous Framework presents stepping stones to guide Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples’ journey together to heal these harms.

Such solidarity requires changes in non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal ways of knowing, being and doing, to enable space for two-way learning, respect and trust to occur. By deeply listening to and drawing from both Aboriginal and Western wisdom, this article presents a way forward to create new knowledge and practice that offer immense benefits to the quality of assessment and support for all Australians living with FASD.

Hewlett, N., Hayes, L., Williams, R., Hamilton, S. et al (2023).

As a Churchill Fellow, my aim is to bring valuable overseas insights to make a difference in local contexts. I enjoy discovering innovative approaches that practitioners can test in their work. However, our knowledge of what works for FASD individuals, especially young people and adults, is lacking in some areas. Research-based evidence is crucial but may not always apply or be effective in Aboriginal communities due to cultural factors and historical trauma.

Therefore, instead of solely relying on evidence-based practices, I think it’s important to implement evidence-informed practices that take into account local knowledge, the expertise of practitioners, and the preferences of the individual and their family. By incorporating these factors, we can develop culturally appropriate strategies that are more likely to be effective in improving outcomes. I summed this up in a quote I gave to FARE for their FASD Awareness Month campaign in 2021:

“There’s nothing I enjoy more than sharing knowledge and learning from others about what is working well. My approach is that any professional who learns more about FASD can come up with better strategies in their own area of practice. I can provide the information, research, evidence and some suggestions – but firmly believe the best suggestions come from the ground up.”

References:

Hewlett, N., Hayes, L., Williams, R., Hamilton, S. et al (2023). Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065215